1. China’s decoupling will be fairly gradual and then very sudden

In early 2019, I remarked on how United States and China were decoupling and how that would only continue:

This “decoupling” from China is still in its early stages, but a UBS “survey of chief financial officers at export-oriented manufacturers in China” late last year found that a third had moved at least some production out of China in 2018 and another third intended to do so this year.

The die has been cast.

US-China decoupling is accelerating and inevitable. Trade relations between the United States and China will lead, and the EU, with trade relations between China and Canada, Australia, Japan, and many other countries soon following. China’s trade relations with these other countries will be greatly impacted in part because they will have little choice if they want to maintain their trade relations with the United States. What we have seen in with Russia’s relationship with the world will become a reality for China as well. This decoupling will be fairly gradual, but at some point it will be incredibly sudden.

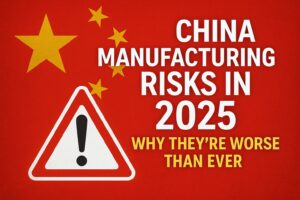

2. US-China trade policies will make China manufacturing untenable

I recently listened to an excellent podcast in which Renaud Anjoran interviewed Andrew Hupert on the always-excellent China Manufacturing Podcast. If you are manufacturing in China, you must listen to the full podcast.

Early in the podcast, Andrew explains how easy it was to find someone to manufacture your products in China and how finding someone to manufacture your products in other countries is considerably more difficult. Andrew’s views on this line up with what I said way back in 2018, in Would the Last Company Manufacturing in China Please Turn Off the Lights, when I first came to believe that China’s role as manufacturer to the world would eventually end:

A story I love to tell is about a conversation I had with a Mexican lawyer friend of mine who studied law in Mexico, China and Canada. One day we were talking about companies moving their manufacturing from China to Mexico and how we both believed those moves would accelerate. My friend then mentioned how Mexico would be doing even better at increasing its manufacturing were it not the worst country in the world at luring foreign company manufacturing. I then said that if Mexico is indeed the worst country at that, it is tied with every other country in the world except for China, which is a distant first.

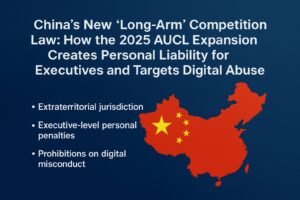

Andrew went on to discuss how increasingly stringent U.S. regulations related to China will eventually make China-US trade so complicated and expensive as to no longer be worth it for most companies:

If you’re importing product into the United States, you are going to need to comply with a lot of new rules. This is going to be your big problem. Compliance is going to be increasingly difficult and expensive. Americans and Europeans will also increasingly need to worry about U.S. tariffs on China goods, which are not going anywhere. I’m not worried about an American or a European procurement manager reaching a deal with a Chinese factory manager. That will continue. The problem will be getting your goods from your Chinese factory to the port in Ningbo or Shenzhen, because of Chinese tit-for-tat regulations. The loser will be procurement.

Companies are used to dealing with Chinese factory managers and engineers, who when faced with a problem, will go off and smoke a couple of cigarettes and come back with a workaround. There is no workaround to excess bureaucracy, other than moving your supply chain.

3. Southeast Asia is probably not the answer to China decoupling

Per Andrew, Vietnam would have been a good alternative to China but it is already full and not looking for the small manufacturing runs that makes China unique. “If you’re Samsung, Vietnam will accommodate you. If you’re Apple, Vietnam will accommodate you. If you have a cool idea for a new pet accessory. Not so much.”

Andrew then talks about how the United States could apply to countries like Vietnam and Thailand the same laws and regulations it applies to China, especially since so many of the products made in Vietnam and Thailand consist of raw materials and/or components from China. If the U.S. starts banning non-market economies or banning anyone whose supply chain runs through China, it’s going to be extremely disruptive for Southeast Asia and for those who do business there.

Even Mexico may not be immune to this:

Mexico’s economy is heavily dependent on its own trade agreement with the United States and Canada — USMCA (the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement). Clause 32 Paragraph 10 of the USMCA says that no member of this treaty can do business with a non-market economy. This is the anti-China clause. But Vietnam is also a non-market economy and Mexico has an agreement with Vietnam via the TPP. It’s up in the air how picky the US wants to be with these new trade laws, but it has a lot to work with.

Andrew then discussed how the 2024 U.S. elections will see politicians competing to see who will support the strongest anti-China trade regulations, and how that will accelerate decoupling. Andrew even went so far as to say that after the 2024 U.S. elections increased costs will make it nearly impossible for many/most businesses to continue their manufacturing relationships with China.

4. China forced labor will be decoupling’s catalyst — Andrew Hupert

After listening to Andrew on Renaud’s podcast, I called him in Mexico.

I first met Andrew in Shanghai in around 2008. Back then, Andrew was teaching international business at NYU and operating a professional skills training firm specializing in mainland Chinese negotiation. Andrew immediately impressed me as someone who sees (or perhaps the better word is confronts) the future before just about anyone else. Last year, Andrew moved to Mexico, based on his belief that China’s trade relations with the world were declining and that other countries — like Mexico — were in the ascendency.

In our call Andrew and I talked about how there will never be another China, how the China of today is not the China of even five years ago, and of how difficult and expensive it is for SMEs to find their own China substitutes. Andrew said that most companies learned about international manufacturing via China and so they now expect the rest of the world to be similar to China and that is just not the case. Companies that have dealt with China should take what they learned about how different a foreign country can be and apply this knowledge to the other countries with which they are now dealing; they now believe they can transfer what they did in China anywhere else, but there will be a learning (education) curve. On both sides.

When China was first getting hot, and companies would come to me seeking legal help with China, I would ask them if their company had ever done any international business, because many had not. Their response was often an apologetic, “Yes, but just with Canada and England.” I would respond by saying, “Good, then you already know to be on the alert for how other countries’ laws and business cultures can differ from those in the U.S.” Today, companies looking to move out of China should know that China’s laws and business culture for the most part do not cross China’s borders, but at the same time, they are equipped to understand country differences.

Andrew and I also talked for a very long time about forced labor in Xinjiang and how that will be the catalyst used to destroy US-China trade relations. We also discussed how difficult it is for companies to prove that their Made in China products were not made with forced labor. One of my law firm’s international attorneys, Fred Rocafort, actually got a forced labor order lifted and that was a huge deal, because it is so rare.

5. China forced labor will soon destroy US-China trade relations — Bloomberg

Bloomberg yesterday came out with a terrific deep-dive article that puts a point on much of what Andrew said in the podcast and my conversation with him. The article, The Dispute Over Forced Labor Is Redefining the Entire US-China Relationship, and like Andrew’s podcast, you really should consume the whole thing. The article essentially says that forced labor from Xinjiang is accelerating decoupling.

The article starts by discussing how China recently appointed a superstar bureaucrat to deal with Xinjiang and this bureaucrat is very publicly touts Xinjiang’s new “anti-poverty” programs. But since the United States sees these “anti-poverty” efforts as a contributor and a smokescreen for forced labor and genocide there will inevitably be big US-China clashes.

Most importantly for those who do their manufacturing in China, the article says that Joe Biden is “putting forced labor at the center of the overall US-China relationship, a move that is already starting to reshape global supply chains”:

Last month the U.S. outlined plans to boost diplomatic pressure on China over what it called “horrific abuses” in the region, adding that it would “fully leverage its authorities and resources to combat forced labor in Xinjiang” — including by lobbying other countries to implement strict measures.

From June 21, the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act will block imports from Xinjiang unless companies can prove they weren’t made with forced labor. The White House is also weighing unprecedented financial sanctions on Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Co., which makes surveillance systems, for linkages to alleged human-rights abuses by the Xinjiang government — a claim the company has repeatedly denied. That could open the door for similar penalties that could cut off other major Chinese companies from the global financial system.

That may just be the start. Since workers and goods from Xinjiang flow across the country, it’s nearly impossible to determine what products are made in the rest of China using what the U.S. deems as forced labor — raising the prospect that the American import ban could eventually be extended to other regions. The Biden administration appears to have given up on trade talks and is now focused on reducing its dependence on China — a position that has bipartisan support in Washington, where both parties are increasingly skeptical of changing the Chinese Communist Party’s behavior through economic engagement.

“We’re breaking these economies apart if China continues this route,” said Sam Brownback, former U.S. ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, adding that companies will need to pick sides. “You can’t stay in that system and be in ours too if they’re going to operate this way.”

China, on the other hand, has every intention of continuing its various “programs” in Xinjiang, and even adding new ones. China also will punish the United States and any other country that challenges China’s Xinjiang actions:

China has repeatedly denied the forced labor allegations, calling them the “lie of the century,” and in April ratified two International Labor Organization treaties dealing with the practice. Still, Xi’s government makes it difficult for foreigners to inspect factories and closely monitors any journalists who visit the region, making it near impossible to verify those claims.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian warned last week that the American import ban on Xinjiang would “severely disrupt normal cooperation between China and the US, and global industrial and production chains.” He said that Beijing would take unspecified actions in response, while accusing the U.S. of seeking to “hobble China’s development.”

The Bloomberg article notes a critical difference between forced labor in China and in other countries:

Unlike in other countries the US has accused of forced labor, the allegations against China are related to government programs seen as charitable within the country. In one example, Xinjiang Goldwind Science & Technology Co., a global leader in wind-turbine manufacturing, said in a 2020 report that it helped with the government’s labor transfer program to eliminate poverty.

Equally importantly, the article notes that forced labor in China goes well beyond just Xinjiang province:

The US says the worker transfers are facilitated by a “mutual pairing program” in which governments and enterprises employ workers either in factories built in Xinjiang or by hiring them to work at plants in other provinces. And the number of Uyghurs being moved away from villages is steadily growing.

And for anyone who wants yet another nail in the coffin of US-China trade relations, the Bloomberg article notes how official Chinese government documents, including the Xinjiang Five-Year Plan through 2025 show that China’s labor transfer program “is set to expand over the next few years” with the goal of “clearing zero-employment families.”

6. Your preparing for China decoupling should start now

If you are having your products made in China, it will likely take you a minimum of six months to find replacement product suppliers outside of China and it is possible you do not even have that long. In any event, if you have not started looking already, you should absolutely start now. For a glimpse at what is involved in moving your manufacturing out of China, I suggest you start by reading the following:

- Moving Your Manufacturing Out of China: The Initial Decisions

- How to Move Your Manufacturing Out of China Safely

- Moving Your Manufacturing out of China: Choose a “Friend”

Just as I predicted above, other countries are quickly following the United States in decoupling from China because of its disdain for human rights. The SCMP (no less) just came out with an article on how it is a near certainty that the EU will this week “designate human rights conditions in Xinjiang as genocide.” Once the EU designates China as engaging in genocide, the odds of EU trade sanctions against China will have just gone way up.