Foreign Language Contracts are Key

I must have told clients at least a hundred times in my career that “foreign language contracts are key.” In this post, I explain why I so often say this and why this is the case.

The Complexity of Language in Legal Contexts

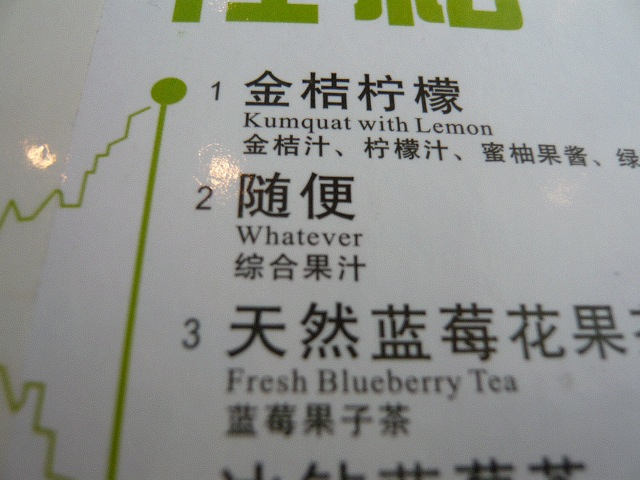

One of the things I often do as a lawyer is review emails before they go to our clients, in large part to make sure everything in them is clear. I once got an email from one of my law firm’s international litigators saying we should “cabin” a particular issue. This lawyer grew up in North Dakota and went to college there. He then went to law school at the University of Minnesota and for many years practiced at a leading Minneapolis litigation law firm. I had never heard the word “cabin” used as a verb and I had to look it up. Google defines this as “to confine within narrow bounds,” but most dictionaries do not have any definition for cabin as a verb at all. Turns out this is Minnesota term since Minnesota is famous for just about everyone having a cabin on one of its 15,000+ lakes.

The Challenge of Legal Fluency Across Languages

I mention this internal email with this litigator to highlight how even among native-born Americans there can be language confusion. Multiply that by one hundred and you have what can and does happen in international transactions, even among people supposedly fluent in both languages.

Take my law firm as an example. We have around half a dozen lawyers fluent in Chinese, and yet only about half of them are fluent enough to be able to craft legal documents in both English and Chinese. The same holds half dozen or so lawyers fluent in Spanish.

Just yesterday a potential client asked me if we had any lawyers who knew Spanish. My response was that we have many. But then later in the call, when we were discussing the need for a Spanish language contract, I told him that less than half of our Spanish speaking attorneys truly have that capability. There is a big difference between being able to watch and understand Lupin in French and being able to have sufficient French language skills to draft an agreement that can determine whether millions of dollars are gained or lost. I was a French major in college and I lived in France for two years, but when it comes time for drafting French language agreements, I always defer to a native French-speaking lawyer. I lived in Spain for a year and I just today hit day 750 on my Spanish Duolingo, but I still need to defer to one of our lawyers for whom Spanish is their native language.

The Importance of Native-Language Contracts

It is important to have your contracts with foreign companies be in their language as well, for a whole host of reasons. The main reason is to achieve clarity.

Having a well-written contract in their native language assures you that your foreign counterparty truly understands what you want of it. It puts the two of you on the same page. For example, if you ask your overseas product supplier if it can get you your product in thirty days, it may answer with a “yes” pretty much every time. But if your supplier signs a contract mandating that its failure to ship your product within thirty days will require it pay you 1% of the value of the order for each day late, you will know it is serious about the 30-day shipment terms. We see this particular issue all the time and it usually stems from the foreign manufacturer believing that you were merely asking whether a 30 day delivery would sometimes be possible.

It is common for companies to come to our law firm wrongly believing they have a “deal” — based entirely on English-language communications — with a foreign company and believing our job as lawyers is merely “to document it.” We look at the deal and immediately note the following:

- There is no way the foreign company would agree to one or more provisions and either it did not (and the foreign company is mistaken) or if it did, but it likely did not understand to what it agreed.

- There are one or more things about the deal that are bad for both sides and both sides would haver benefitted by changing those.

- There are one or more things that are completely illegal in one or both countries.

- There are one or more things that are completely unworkable or nonsensical in one or both countries.

Sometimes these companies will have been negotiating for months (even years) and will have made many trips back and forth between the two countries, and everything they have done is either completely unworkable or illegal.

The Solution: Truly Bilingual Negotiation and Involvement

What should these companies have done? They should have spent the extra time and money to use truly bilingual negotiators from day one and every single step of the way and — to the extent possible — the true decision-makers should have been intimately involved in negotiations from day one and every single step of the way as well. This usually costs more in time and money in the short term, but it nearly always ends up saving way more time and money in the long term.