He will hold onto power, but for how long I don’t know. It’s like the stock market. I can right now confidently tell you that it will go up. I can also confidently tell you that it will go down. And with either prediction my confidence is justified because I’ll be right. But so what? My prediction isn’t worth anything because without a reasonably accurate prediction on timing, my predictions are of no value whatsoever.

Are you old enough to remember Peter Lynch? I was a big follower of him back when he was one of the top two or three investment gurus. Lynch once said that “If You Spend 13 Minutes A Year On Economics, You’ve Wasted 10 Minutes.” What he was saying is that when investing, you cannot predict the economy with sufficient accuracy to time the market, so you should instead focus on individual stocks.

I think the same is true in predicting whether or not a government is going to fall. I lived in Istanbul, Turkey, for a year before there was a military coup. And to say I was obsessed with Turkish politics during that time would be an understatement. I read pretty much everything on Turkish politics (in English and Turkish) and talked with pretty much everybody. And during that year, about half the people insisted a coup was imminent and others insisted that it wasn’t. Even though a coup did happen during the final week of my year in Turkey, both sides were mostly wrong. Though a coup finally did happen, those who said it was imminent had been saying that for many years and those who were predicting no coup were obviously wrong as well.

And take Tunisia. If you had asked me a week before the Tunisian/Jasmine revolution to list the twenty countries most likely to see their leader deposed in the next month, Tunisia literally would not even have occurred to me. I often say that if Mohamed Bouazizi had not lit himself on fire on December 17, 2010, there probably would not have been any revolution at all in Tunisia.

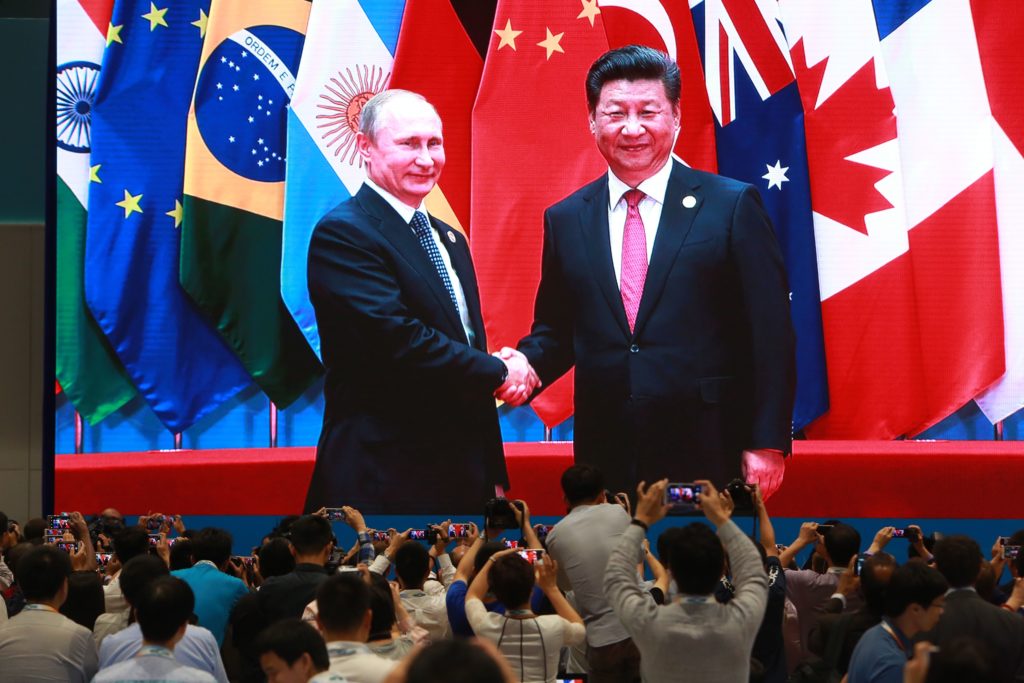

And get this. I’m convinced that without the Tunisian revolution, President Xi might not have assumed power in China and would not have been able to take on the power he now has. Tunisia’s revolution scared the hell out of the CCP elites and convinced them that they needed to get tougher so as to remain in power. Xi was their choice for that and their fear has led them to give Xi Mao-like power.

Anyone who claims they could have or did predict the self-immolation in Tunisia and Tunisia’s subsequent revolution and its subsequent impact on China is lying.

So why am I writing about President Xi today? Is it because of the upcoming October 16 Party Congress. Well, no. Not exactly.

It’s because I read three fascinating articles today and thought about how they fit together to help explain China.

The first article (just two hours old) comes from the Washington Post: “Putin confronted by insider over Ukraine war, U.S. intelligence finds.” The gist of this story is that a “member of Vladimir Putin’s inner circle has voiced disagreement directly to the Russian president in recent weeks over his [Putin’s] handling of the war in Ukraine, according to information obtained by U.S. intelligence. Per the article, this indicates “turmoil” within Russian leadership. The article then notes that this “new intelligence, coupled with comments from Russian officials, underscores divisions within Putin’s upper echelon, where officials have long been loath to bring bad news to an autocratic Russian leader [Putin]. . . . The article then goes on to discuss how — if at all — this discontent will impact Russia’s war against Ukraine and internal Russian politics. This article reinforces what has become my most common refrain in 2022 (from Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises), “gradually then suddenly.”

The second article is from The New York Times: Nobel Peace Price Prize is Awarded to Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian Activists. Per the article, this year’s Nobel prize is a “rebuke to Putin”:

“The Peace Prize laureates represent civil society in their home countries,” Berit Reiss-Andersen, the chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, said in announcing the awards. “They have for many years promoted the right to criticize power and protect the fundamental rights of citizens.”

The committee said it had chosen the three laureates because it wanted to honor the champions of “human rights, democracy and peaceful co-existence” in the neighboring countries of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine.

Their work has taken on new significance since February, when President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia invaded neighboring Ukraine, displacing millions of people and destabilizing the entire region.

The prize was an implicit rebuke to Mr. Putin, whose tenure has been punctuated with violent crackdowns on dissidents and critics at home — and whose 70th birthday was on Friday, an overlap noted by several observers.

I’m always impressed by those who fight for human rights in countries like Russia and Belarus where doing so puts one’s life at risk — the Belarusian prize winner is in jail. BUT, in reading this article and in thinking about the prize, I get what the Nobel committee was thinking in terms of Russia, but it would have been nice had the prize also gone to human rights activists from countries like China and Myanmar, where there are many who speak up despite the considerable risks. Oh well.

The third and last article I read (also from this morning) was “China’s Lockdowns Creating Chaos Ahead of Top Meeting,” from The New York Times. From this article I pulled the following three things:

One, “let them eat cake.” China’s lockdowns disproportionally and not coincidentally have impacted the cities/regions the CCP most wants to “put in their place”: Tibet, Xinjiang, and Shanghai. This article nicely summarizes the CCP’s fanatical effort to to “stop the spread of the coronavirus from ‘spilling over’ to Beijing, the capital, where the meeting will be held. … The authorities are sticking closely to their ‘zero Covid’ policy of eliminating infections, despite the enormous economic and social cost of the strategy. Mr. Xi has made ‘zero Covid’ a political imperative, linking support for the policy to support for the Communist Party, as he looks to hail China’s success in curbing infections as a sign of the superiority of Beijing’s authoritarian system.”

The article does not mention how if the CCP had not so arrogantly and inhumanely rejected the use of effective vaccines from the West, it likely would not be in this situation. See e.g., Moderna refused China request to reveal vaccine technology.

Just as is true of Russia, the overriding attitutude in the halls of power in China these days is the people be damned. “Let them eat cake.”

Two, China’s COVID crackdown is accelerating. China’s efforts to rein in COVID have gotten so out of hand that the crackdown itself is actually (and admittedly) helping to fuel COVID’s spread. Liu Sushe, the vice chairman of Xinjiang, admitted that anti-COVID “measures, such as compulsory mass testing, may have even contributed to spreading the virus, as some health workers who were not wearing proper protection became infected themselves.”

And China is intentionally and explicitly going for “overkill” on its COVID reduction efforts:

At a meeting chaired by Sun Shaocheng, the top party official of Inner Mongolia, officials were instructed to stop infections by “killing chickens with a knife for slaughtering cows,” a play on a Chinese idiom, to indicate that overkill was desired. “Act faster, prevent spread and spillover, especially to Beijing,” an official readout said. Since then, several cities and counties in the region have been placed under lockdown.

Overkill is increasingly the norm. In the tropical island province of Hainan, often dubbed the Hawaii of China, the authorities ordered mass testing after just two cases were detected on Monday. The province has only recently emerged from a lockdown in August of the popular tourist city of Sanya, which trapped tens of thousands of travelers.

Though I claim no expertise in predicting China politics and power (see above), I do claim to have been unerringly accurate in predicting what would happen with COVID in China. In December, 2021, in Omicron and Supply Chains: Buckle Up, I made clear that China would unrelentingly try to contain COVID, that it would fail to do so, and that the repercussions on foreign manufacturers and on China’s economy would be great. I mention this because many are predicting that China will ease up on COVID after the Party Congress and I am pretty confident that is not going to happen. There is a big difference between predicting what the CCP will do (which is actually pretty easy because it is usually quite clear on its policy objectives and on its planned actions) and on whether the CCP will remain in power.

Three, gradually and then suddenly. Turkey. Tunisia. Russia. China. It is virtually impossible to predict the overthrow of a regime, especially an authoritarian one. There are visible cracks in China’s (and Russia’s) regime and those cracks go well beyond COVID and the economy, but it is impossible to predict whether those cracks will become massive fissures large enough to bring down the Xi regime. But by the same token, one should not rule out this possibility either. Will President Xi remain in power? No. will President Xi be gone in a day, a week, a month, a year, or a decade? Yes.

What do you think?