In a recent LinkedIn conversation someone raised the possibility of the “Made in GBA (Greater Bay Area)” label replacing “Made in Hong Kong” and “Made in China” as a country of origin marking in South China. It’s an intriguing idea that would certainly reflect the spirit of the GBA project. Could “Made in GBA” actually be a thing? The short answer, at least as far as the United States is concerned, is NO.

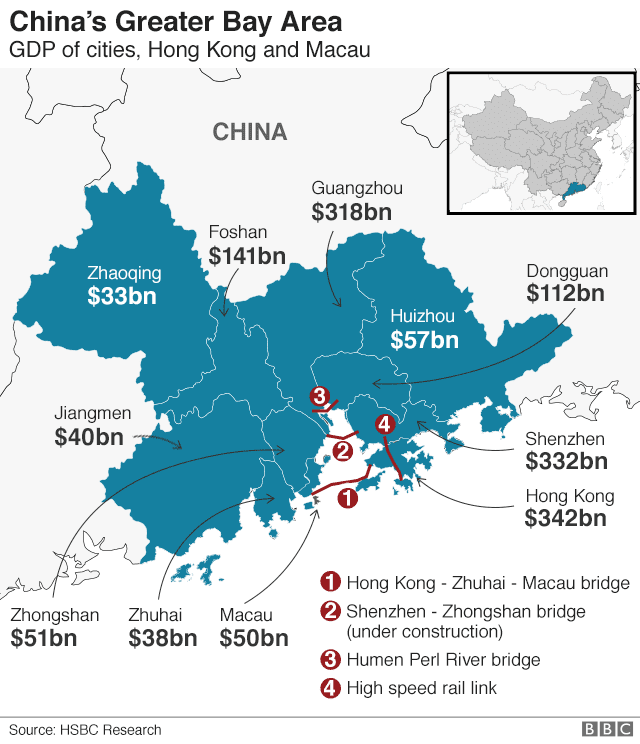

The Greater Bay Area. If you’re not familiar with the GBA (in Chinese, 粵港澳大灣區), it “comprises the two Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau, and the nine municipalities of Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Foshan, Huizhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Jiangmen and Zhaoqing in Guangdong Province”. China wants to “fashion them into what it calls a ‘Greater Bay Area’ to rival San Francisco, New York and Tokyo as a powerhouse of innovation and economic growth”.

At the moment, the GBA is just an “ambitious but vague” plan, but no expense has been spared in building the physical infrastructure that undergirds it. Hong Kong is now connected to China’s high-speed train network, allowing passengers to get to Beijing in nine hours. The Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge, “designed by the Chinese government to bind the former European colonies of Hong Kong and Macau closer to the motherland”, is now open.

The vision behind the Greater Bay Area plan is clear: It seeks to subsume Hong Kong and Macau into the surrounding Mainland areas, diluting their special character and moving away from the Two Systems model. At the same time, it would allow these nearby areas to directly harness Hong Kong and Macau’s strengths as contributors to Mainland China’s development.

Going back to the original point, a “Made in GBA” label would make sense from China’s point of view. On the one hand, it would allow products made in the GBA’s Mainland Chinese cities to enjoy the same designation as products made in Hong Kong, a well-regarded, advanced, high-income economy. Note that very little actually gets made in Hong Kong. At the same time, it would nominally link at least some of Hong Kong’s economic activity to that of the GBA at large, bringing a whiff of prestige to locales across the border typically associated with low-cost manufacturing. No longer would the story be one of Hong Kong companies shifting their production to Guangdong to enjoy lower costs and laxer regulation—it would all be part of a larger whole.

U.S. Country of Origin Marking Rules. United States law requires “every article of foreign origin… imported into the United States shall be marked in a conspicuous place as legibly, indelibly, and permanently… as to indicate to an ultimate purchaser in the United States the English name of the country of origin of the article”. 19 USC § 1304(a). United States Customs and Border Protection regulations define “country” as “the political entity known as a nation”, adding, “Colonies, possessions, or protectorates outside the boundaries of the mother country are considered separate countries.” 19 CFR § 134.1(a). The name of a colony or similar territory must be “sufficiently well known to ensure that the ultimate purchasers will be fully informed of the country of origin”. Where “the name appearing alone may cause confusion, deception, or mistake, clarifying words shall be required”. 19 CFR § 134.45(d).

There is no need to consider the thorny issue of whether Hong Kong ceased to be a colony in 1997 when its sovereignty was transferred to China because specific guidance regarding Hong Kong is found in the United States-Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992 (“Act”), which provides that the U.S. “should continue to treat Hong Kong as a separate territory in economic and trade matters, such as import quotas and certificates of origin”. The United States-Macau Policy Act of 2000 provides for similar continuity for Macau.

“Made in GBA” would make it impossible for U.S. Customs to treat Hong Kong or Macau as separate territories from China. Would GBA products be treated as Hong Kong or Chinese products for tariff purposes? This matters. In addition, it would confuse ultimate purchasers, who may not be able to know if the product was made in Hong Kong or Guangdong (though, again, it’s highly unlikely that a manufactured good these days will have actually been made in Hong Kong).

The United States-Hong Kong Policy Act grants the U.S. President authority to issue an executive order to suspend differential treatment for Hong Kong if it “is not sufficiently autonomous to justify treatment under a particular law of the United States, or any provision thereof, different from that accorded the People’s Republic of China”. The United States is a hair-trigger away from the proclamation of such an order. It is certainly in the palette of options the U.S. government is considering in response to China’s crackdown in Hong Kong.

Would such a proclamation mean the end of “Made in Hong Kong”? Not necessarily. The use of Scotland as a country of origin has long been acceptable to U.S. Customs and Border Protection so there is some precedent for allowing subnational entities other than colonies and similar territories to be treated as countries for country of origin purposes.

It makes sense for U.S. Customs to accept “Made in Scotland” labels because Scotland enjoys broad name recognition in the U.S. and there is little risk of confusion. Arguably, the same is true of Hong Kong. In fact, American consumers historically have had great exposure to “Made in Hong Kong” products. Even as the city’s political situation changes, its name will remain “sufficiently well known”.

To be fair, Scotland and Hong Kong are probably the exceptions that prove the rule. The use of just about any other subnational entity’s name would likely cause considerable confusion. That is certainly the case with the Greater Bay Area as few Americans outside China-watching circles even know what it is.