Currently, the number one film in China is the smash hit Hello Mr. Billionaire (US$306M and counting). It’s a comedy about a hapless soccer player who stands to inherit 30 billion RMB, but only if he can spend 1 billion RMB in a month (albeit with a number of complicated conditions, like no gambling, donating the money, or purchasing illegal substances).

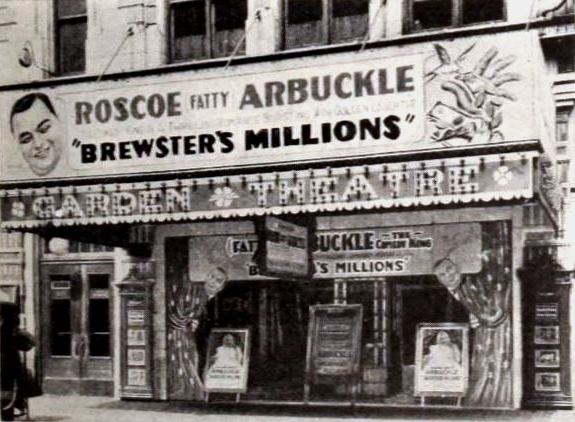

If the story sounds like déjà vu all over again, that’s because it’s the same plot as a 1985 Universal movie starring Richard Pryor called Brewster’s Millions. The idea for Hello Mr. Billionaire originated with Universal, which was seeking to exploit their back catalog by remaking movies for a Chinese audience. It’s a brilliant strategy when it works, except that it didn’t actually work for Universal: they decided not to finance the remake and merely allowed the filmmakers to use some of the plot points from the 1985 film.

The track record of Chinese remakes is decidedly mixed. In 2017, Disney remained highly involved in The Dreaming Man (a remake of the 1995 Sandra Bullock film While You Were Sleeping) but it barely registered at the box office. Before that, the 2004 film Cellular was remade in 2008 and bombed; the Coen Brothers’ 1984 film Blood Simple was remade in 2009 by Zhang Yimou and enjoyed modest success; and the 2000 film What Women Want was remade in 2011 and basically broke even. It only takes one success to start a trend, though, and the outsize profits of Hello Mr. Billionaire will surely lead to similar remakes being fast-tracked.

But Hello Mr. Billionaire is not just any remake. It’s based on the 1902 novel Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon, which has been adapted into a film at least 12 times and in multiple countries. Sure, the story is fun, but I suspect the real reason it’s been remade so often is that the IP is free – the book’s copyright has expired and the story has been in the public domain for years. Thus, when Universal decided not to fund Hello Mr. Billionaire, the only chain of title issues the filmmakers faced were with respect to plot points or characters that solely appeared in the 1985 film. (The filmmakers may have had other contractual obligations to Universal, but that’s a separate matter.)

In China: Published work enters the public domain after the life of the author plus 50 years

Let’s thicken the plot even further. China and the US are both signatories to the Berne Convention, but they don’t have the same rule when it comes to the expiration of copyright. The basic rule in China is that a published work enters the public domain after the life of the author plus 50 years (i.e., the minimum protection under the Convention); the basic rule in the U.S. is the life of the author plus 70 years. Both countries have numerous exceptions to the rule, which in the U.S. are even more advantageous to copyright holders.

It remains unclear whether China would apply its own rule or the U.S. rule for a work created in America — say, a book or play or other source material for a movie. It may seem like a moot point because most movies are created for an international audience, but the Chinese film audience is so big now that a Chinese movie only needs to succeed in China. As of December 31, 2018, the works of any author who died in 1968 will arguably be in the public domain in China.

The larger question is whether Hollywood will view this as a threat, an opportunity, or both.