Yesterday, on June 30, the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School announced the launch of a three-year research initiative, the Project on Psychedelics Law and Regulation (POPLAR). The initiative will be led by Harris Sliwoski attorney Mason Marks, who also serves on the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board.

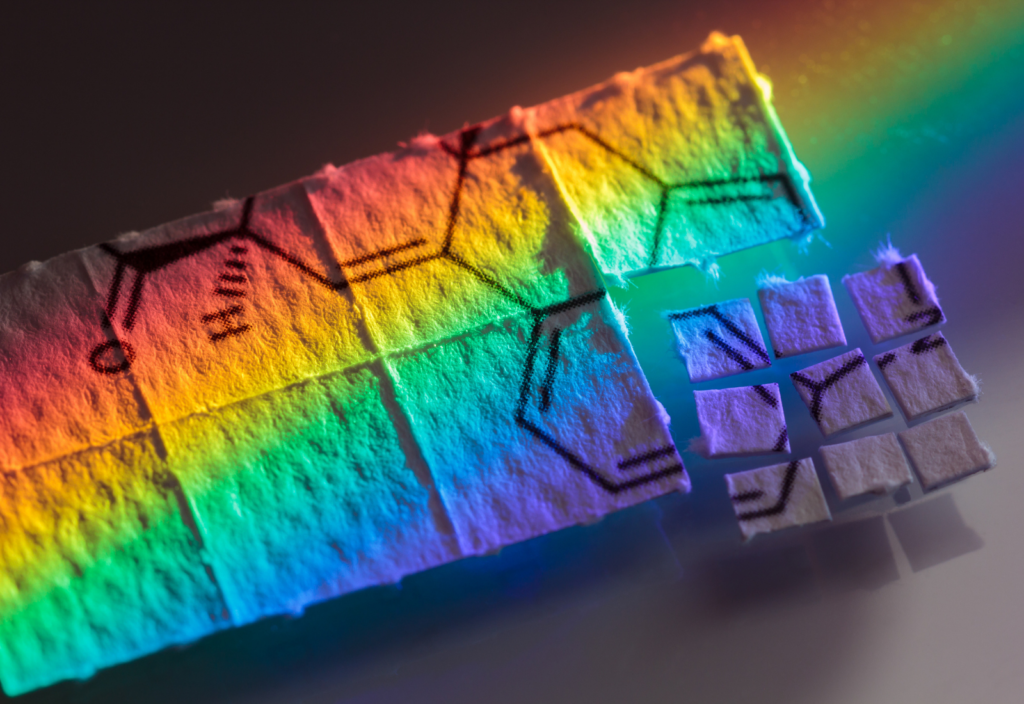

As we’ve covered extensively on this blog, the FDA has designated MDMA a breakthrough therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder, and it has designated psilocybin as a breakthrough for treatment-resistant depression. These designations indicate that psychedelics may represent substantial improvements over existing treatments for mental health conditions. Many other psychedelics, including ibogaine, ketamine, and dimethyltryptamine, are the focus of ongoing psychiatric research and commercialization efforts. The research hurdles remain high, but momentum clearly favors the researchers.

Psychedelics also have implications beyond their clinical relevance: they may help researchers better understand consciousness and the human brain. Additionally, their regulation highlights many shortcomings of current U.S. health care and public health policy. For instance, their restricted status makes psychedelics difficult to study, and their commercialization by large firms highlights key concerns with pharmaceutical development, drug enforcement policy, research ethics, and intellectual property law.

In the following interview, which has been edited and condensed, Harris Sliwoski attorney Mason Marks, MD, discusses POPLAR with Flom Center Communications Associate Chloe Reichel. Dr. Marks leads this research project as a Senior Fellow at Harvard Law School. A longer version of this interview is available on the Petrie-Flom Center Bill of Health Blog.

Chloe Reichel: Can you describe the primary goals of POPLAR?

Mason Marks: The project’s goal is to promote safety, innovation, equity, and accessibility in emerging psychedelics industries. POPLAR will publish original law and policy research. We will also translate existing clinical research, making it more accessible to courts, lawmakers, federal agencies, and the public. Fundamentally, we aim to correct misinformation and advance evidence-based psychedelics policies and regulation.

CR: Can you describe the existing landscape of psychedelics research? What barriers exist to conducting psychedelics research?

MM: The Schedule I status of psychedelics is a significant legal barrier. Until the early 21st century, it prevented all psychedelics research. Things have changed a little in the past twenty years, when the DEA gave some researchers permission to study limited amounts of certain psychedelics. Now several trials have been completed, with promising results, and there are many ongoing studies. But they remain relatively small, in part because the DEA limits the amount of psilocybin and other psychedelics that can be produced each year. Moreover, due to their Schedule I status, it can be difficult to get research programs focused on psychedelics started.

Because psychedelics are misunderstood, and they remain heavily stigmatized, federal funding is not readily available for research. As a result, many researchers are deterred from entering the field, and for similar reasons, universities are often hesitant to support this type of work. Nearly all research is funded by private donors through corporate sponsored research centers.

CR: Why does it matter who is funding and conducting psychedelics research?

MM: Under existing regulation, only well-capitalized private companies can fund psychedelics research, and, to a large extent, they control the research agenda and influence drug policies. When wealthy private companies fund most research on psychedelics, have special permission from the DEA to handle them, and hold associated patent rights, they are shielded by several layers of government-granted monopolies. They can use that privileged position to shape the narratives surrounding psychedelics, influence government officials, buy the loyalty of scientists, and charge whatever prices they want for psychedelic therapies. The restricted Schedule I status of psychedelics serves their interests, because it helps maintain their dominant positions.

However, the public health problems that psychedelics may address, such as the worsening drug overdose epidemic, are too vast and important to leave to private companies with a vested interest in the status quo. When it comes to problems of this magnitude, we don’t want industry shaping the entire agenda. It is preferable to have a diverse array of scientists and other stakeholders shaping the narrative and steering public policy.

CR: Who might benefit from the legalization and commercialization of psychedelics? Who might be left behind?

MM: Who stands to gain? The pharmaceutical companies, venture capitalists, and patent holders certainly stand to benefit from commercialization. In contrast, it is unclear to what extent people most in need of psychedelic therapies will benefit. If these treatments are too expensive, few people will be able to afford them. Widespread insurance coverage for psychedelics seems a long way off, further restricting access, and requiring patients to pay cash. Unless something changes, corporations may experience the greatest benefits of psychedelics commercialization.

These problems are not unique to psychedelics. In recent years, we’ve seen drug prices rise, even for essential medicines like insulin, which have been around for decades. Some life-saving medicines, such as biologic drugs for muscular dystrophy, can cost hundreds of thousands or millions per year, or even per dose. These trends reflect deep, systemic problems with the health care system that the emerging psychedelics industries highlight. But there are also certain features of psychedelics that warrant special attention.

For instance, the long history of prohibition and punitive drug enforcement has caused irreversible trauma that disproportionately impacts vulnerable groups including communities of color and people with disabilities. By preventing research for decades, prohibition also likely deprived people with mental health conditions of more effective therapies, costing countless lives and billions of dollars over the years.

There are other groups that could be left behind. Communities who have used psychedelics for hundreds of years may view patents and psychedelics commercialization as forms of exploitation and theft of their sacred knowledge and technologies. These groups will potentially be marginalized in the push to commercialize psychedelics.

CR: Psilocybin is a psychedelic produced by mushrooms. Can you patent a mushroom?

MM: A mushroom that occurs in nature cannot be patented. There are several limits on patentability, some of which are called the judicial exceptions to patent eligibility. These exceptions were shaped by over a hundred years of federal and Supreme Court precedent, and they prohibit patents on abstract ideas, products of nature, and natural phenomena. If something falls into one of these categories, it cannot be patented.

So, if you go into the forest and pick a mushroom, you can’t receive a patent because it’s a product of nature. You haven’t invented anything. However, if you modify the mushroom in some way, so that it’s different from the version found in nature, through genetic manipulation for example, then you could patent your creation. Whether or not you modify the mushroom, you could also patent various methods of growing it and utilizing it, because in those instances, you aren’t patenting the product of nature itself, but a method of producing or using it.

Compass Pathways was able to patent a crystalline form of psilocybin because that form does not occur in nature. However, it remains to be seen whether such a patent could withstand a challenge to its validity. Patents can be invalidated in court, for instance, if they lack novelty or would be obvious to someone skilled in the relevant technological field.

CR: As interest grows in the therapeutic properties of natural substances, concerns about bioprospecting and biopiracy are growing. Can you explain these practices and the associated concerns?

MM: Bioprospecting is the practice of searching for natural products that might have some kind of industrial or therapeutic application. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, bioprospecting is very important because it allows humanity to benefit from natural resources.

The more concerning term is biopiracy, defined as stealing the inventions or practices of Indigenous communities, typically bringing them back to Western societies, and patenting or commercializing them without adequately acknowledging, compensating, or obtaining permission from the communities that created them. Unfortunately, there are many examples – in Peru, for example, the psychedelic brew known as ayahuasca has been commercialized by Western companies. There are growing concerns that the endangered peyote cactus, used by Native American churches, will be commercialized, overharvested, and ultimately destroyed.

CR: What do you hope the impact of this project will be?

MM: Right now, there are a handful of psychedelics research centers at major universities around the country. However, they all focus primarily on clinical research, mostly surrounding trials of MDMA and psilocybin. Surprisingly, there is little systematic analysis of the law and policy issues raised by psychedelics, which is likely due to longstanding stigma.

POPLAR will fill this gap in psychedelics research. If psychedelics law and policy is not analyzed and modernized, the field will not progress. Researchers, businesses, and the public will continue to be constrained by social and legal barriers that have existed for fifty years.